Burnt to the Core

Luke Henderson, Year 12

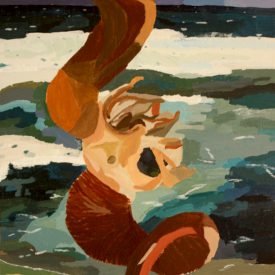

The Xanthorrhoea, commonly known as the black boys. Seemingly identical yet different. The little trees fascinated William. Simple to look at, but sharp to touch. To William they looked like miniature trolls, moving into battle. It was evident that his little brother Alex had a different view, as he ran around growling with them in between his fingers like wolverine claws.

“RARR!” Alex growled at his brother. Alex amused William. That tree was an Australian icon in the eyes of most, but a weapon in his brother’s eyes.

“ROAR!” William startled his brother with an unexpected shriek. They had a pretty good relationship for two stepbrothers and they managed to get on, despite their seven-year age gap.

“AY!” William’s stepfather slid out of their Ute in his regular grump. “Stop playin’ with those dumb sticks,” he grunted. “I’m not gonna be cleanin’ up your blood when ya slip.” He moaned at the thought of any actual labour. The boys would be more surprised to see him sober, than in his regular swaying back and forth state that he seemed to wake up with. His pot belly revealed the thick gut that was hanging below his ACDC t-shirt. The only thing that William admired about him was his ability to grow a thick beard. It nicely complemented the drunken hobo look he was obviously going for.

“Alright, Derek, calm it down,” whispered William, waiting for his inevitable reaction.

“Just ’cause you’re not mine, don’t mean I can’t hit you,” Derek barked back. He waddled over to William, with his hand ready to snap William’s jawline.

“That’s enough, Derek!” commanded William’s mother from the Ute.

“Yes sir,” Derek replied patronizingly, as he waddled back towards the car.

William did not understand why his mother re-married such a pig. At least he got a brother out of it.

It was supposed to be a quick trip down to the Eagle Bay Beach, but Derek’s reckless driving drove them off the road and into the bush. And now the car wouldn’t move. Trapped in the middle of the bush on a forty-degree day, both boys chose to wait outside rather than risk being cooked alive by the blazing sun, as it heated up the metal frame of the broken down car. The roadside assistance was not reliable down South and the boys knew it could be up to an hour before any progress could be made.

“RARR!” Alex shouted at his brother. Oblivious of his Dad’s orders, he circled Alex like a lion, preparing its prey for dinner. William turned and lightly tackled his brother to the ground. The two of them wrestled in the hot dirt, until both of them were too hot to move, their sweat forcing the sand to stick to them. “I’m Sandman,” Alex announced, standing up triumphantly. The joy in his faced was quickly transformed into a pale expression of shock. William turned to follow the gaze of his brother.

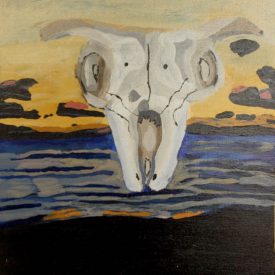

“That’s a lot of smoke,” Alex whimpered.

“Fire!” William shouted, releasing all the stored energy inside his body.

Derek launched himself out of the Ute and shared Alex’s expression. For the first time he actually showed William an emotion other than disappointment.

“Run!” he shouted, leaving his family behind in a hurry.

“Come on, Alex,” William insisted, lifting his brother to his feet and grabbing his hand.

“Come on boys,” their mum calmly pleaded. She jumped out of the car and signalled for the boys to quickly follow her. The boys ran with their mother down the road towards the ocean, where they were initially intending to go to for a cool swim. The adrenaline pumped through their bodies allowing them to run at a lightning pace.

Much to William’s expectation they caught up to Derek, who was throwing up booze he had just consumed.

“I waited for ya,” Derek said unconvincingly, whilst gasping for air. “Can ya give ya ol’ man a hand?” he pleaded reaching his arm out. The boys lifted him up in a hurry.

“Come on, we’ve got to go, it’ll catch us if we take too long,” William insisted. The family started to run together down the road.

The sound of a car horn came around the bend from behind, bringing a glimmer of hope for the family.

“Oh, thankya Jesus!” Derek leapt to his feet with joy.

The driver rolled down the window as he slowed to a stop.

“We’ve already got three families in here, we’ll only be able to fit one of you into the boot,” he explained.

“Take me, I’m sick,” Derek jumped into the boot without hesitation. “You’ll run faster without me,” Derek added trying to gain some form of respect for himself. The boys and their mother ignored the heat and ran down the road, following the now disappearing car. William picked up his struggling brother and tried to assist his mother to safety.

“We’re almost there,” William insisted, as a black layer of smoke covered them. Their mother started choking and fell to the ground. The black smoke made it impossible for the boys to see their mother.

“Mum!” William shouted, as he began to choke on the smoke. His little brother was no longer conscious, so William forced himself to continue and push his way out of the bush. He could faintly hear the sound of sirens in the distance.

Paramedics rushed to the aid of the two boys who were showing limited evidence of life and they were lifted from the scene. The rich green vegetation had been burnt to the core.

“Where is she?” Derek questioned William who was currently wearing an oxygen mask. William did not have the stamina to reply. “Where is she?” Derek yelled.

William shook his head.

“You left her!” Derek screamed. “Your own mother. You were too selfish to help her to safety,” Derek cried.

“You Devil!” Derek squawked.

William passed out.